|

(c)

Copyright Bartók Archives of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Institute for Musicology, 2004-2005

Dichotomies

|

| |

|

|

“Kodály and I

wanted to make a synthesis of East and West … Because of

our race, and because of the geographical position of

our country, which is at once the extreme point of the

East and the defensive bastion of the West, we felt this

was a task we were well fitted to undertake. But it was

your Debussy, whose music had just begun to reach us,

who showed us the path we must follow. And that, in

itself, was a curious phenomenon when one recalls that

at that time so many French musicians were still held in

thrall by the prestige of Wagner. ... Debussy’s great

service to music was to reawaken among all musicians an

awareness of harmony and its possibilities. In that, he

was just as important as Beethoven, who revealed to us

the meaning of progressive form, and as Bach, who showed

us the transcendent significance of counterpoint. ...

Now, what I am always asking myself is this: is it

possible to make a synthesis of these three great

masters, a living synthesis that will be valid for our

own time?”

Serge Moreux, Béla Bartók (London,

1953), 92

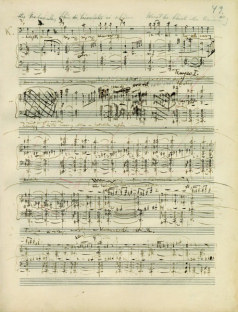

On one of these days, as if receiving inspiration

from above, I suddenly realized the indubitable

necessity that your piece can only consist of 2

movements. 2 contradictory images: that’s all.

Bartók to Stefi Geyer about his early

Violin Concerto written for her, December 21, 1907,

in Béla Bartók, Briefe an Stefi Geyer (Basel, 1979), 56,

facs. 21

|

|

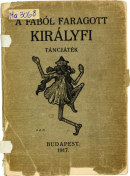

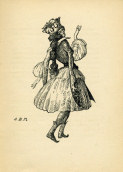

I began to compose the ballet even before the war,

then I put it aside for a long time. I went through a

lot of anxiety. Last season, István Strasser performed

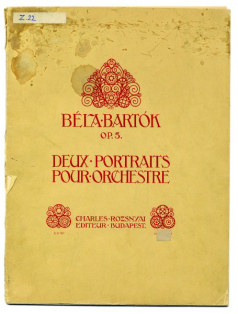

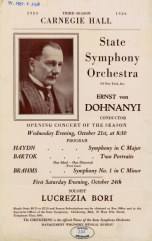

my symphonic work Two Portraits; it was the first time I

heard the second part (“Caricature”) played by

orchestra. That inspired me to go on with the score of

the The Wooden Prince...

Bartók, “About The Wooden Prince”

(1917), in Béla Bartók Essays, ed. Benjamin Suchoff

(London, 1976), 406, revised

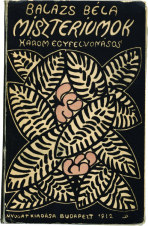

It may sound peculiar but I must admit that the

preterition of my one-act opera Bluebeard’s Castle prompted me to

write The Wooden Prince. It is common knowledge

that this opera of mine failed at a competition; the

greatest hindrance to its stage production is that the

plot offers only the spiritual conflict of two persons

and the music is confined to the depiction of that

circumstance in abstract simplicity. Nothing else

happens on stage. I am so fond of my opera that when I

received the libretto of the pantomime from Béla Balázs,

my first idea was that the ballet—with its spectacular

picturesque, richly variegated actions—would make it

possible to perform these two works the same evening.

“About The Wooden Prince,” in Béla

Bartók Essays, ed. Benjamin Suchoff (London, 1976), 406

|

|

|

|

|

The constructive strength of the music [of

Bluebeard’s Castle] asserts itself even better if we

hear The Wooden Prince after it. This ballet

balances the disconsolate adagio of the opera

with a playful, animated allegro contrast. The

two together merge into one, like two movements of a

giant symphony.

Zoltán Kodály, “Béla Bartók’s First

Opera” (1918), in The Selected Writings of Zoltán Kodály

(Budapest, 1974), 85, slightly revised

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

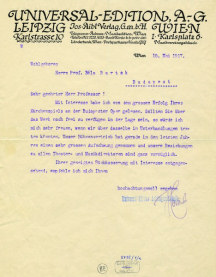

The reviews of Bluebeard were

better then those of the Wooden Prince...

However, this year’s greatest success for me was

not this, but rather my success in entering into

a long-term agreement with a first-rate

publisher.

As far back as January “Universal Edition”

(Vienna) made me an acceptable offer. Now, after

protracted negotiations, we have agreed on

everything... This is of great significance

because for approx. 6 years nothing of mine has

appeared—thanks to our home publishers—and

because a foreign publisher has perhaps never

before approached an Hungarian musician with

such an offer.

To Ioan Buşiţia, [June 6, 1918], in Bartók

Letters. The Musical Mind,

ed. Malcolm Gillies

and Andrienne Gombocz, unpublished

|

|

|

|

As regards the lecture, I should like to ask you (1) not to overemphasize the folkloristic aspect of

my work;

(2) to underline that I never use folk melodies in my

stage works just as I never do in my other original compositions; (3) that my music is throughout tonal and (4) has nothing to do with the “objective” and

“impersonal” tendency (so in the last analysis it is not “modern” at all!)

[.]

Bartók giving advice to conductor Ernst

Latzko, December 16, 1924, German original

in Béla Bartók Briefe, ed. János Demény (Budapest,

1973), vol. 2, 50

|

|

|

| |

|

|