History of the Archives

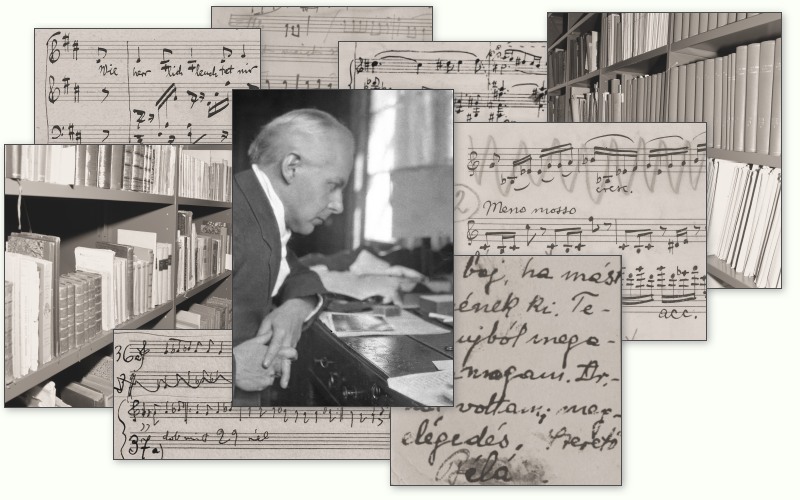

The Bartók Archives of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences – originally a multi-profile musicological research institute – was opened on September 25, 1961, in the Castle district of Buda (Országház utca 9., Budapest I, in the neighborhood of the present location), under the directorship of Bence Szabolcsi. The Bartók Archives proper was an independent department of this institute. Denijs Dille, a Belgian Bartók expert, sought out for this post by Zoltán Kodály, became its first Director. The so-called “Bartók Hagyaték” (Bartók estate), owned by Béla Bartók Junior (d. 1994) but deposited as a permanent loan to the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, formed the kernel of the collection. This was extensively enlarged with material from Bartók’s Hungarian publishers (Rozsnyai, Rózsavölgyi, etc.), and private collectors, including Mrs. Emma Kodály. Unfortunately, the Archives was practically cut from the American sources. As a result of the policy of the Budapest and New York Bartók archives, aggravated by cold-war politics, family and legal matters, for two and a half decades the autograph sources were available for the international community of scholars and the public only to a very limited extent.

In 1972 László Somfai, first Dille’s assistant (1963–), became the Director of the Bartók Archives. In 1984 the Bartók Archives, as part of the enlarged and renamed Institute for Musicology (incorporating Kodály’s one-time Folk Music Research Group too), moved to its present address.

In 1987–88, after the death of Bartók’s widow Ditta Pásztory (1982) and the following legal procedure, the former New York Bartók estate and archives came into the hand of the younger son of the composer, Peter Bartók, who sent photocopies of the primary sources of the compositions to the Budapest archive in 1988 in order to aid the work on the preparation of the complete critical edition and related studies. As a result, in the Budapest Bartók Archives the complete basic primary source material is either accessible to the qualified scholar or information on the whereabouts of the here missing documents is available.

Former members of Somfai’s staff from the 1970s–80s who accomplished crucial Bartók studies include Vera Lampert (Brandeis University, Library), Tibor Tallián (Institute for Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences; F. Liszt Academy of Music), András Wilheim (Budapest), Klára Móricz (Amherst, Mass.), Adrienne Gombocz (editing Bartók's letters), Sándor Kovács (folk-music collection), and László Vikárius (source studies).

In the first period of the institute the six-volume series of Documenta Bartókiana and a thematic catalogue by Denijs Dille of the juvenile compositions established a new standard in source-oriented Bartók documentary studies. A close contact with performance practice, advising recording projects, and the edition of Bartók’s complete recordings also belong to the profile of the archive. The Bartók Archives, although not linked with a university, due to the unique material and the expertise of its fellows, continuously support graduate and postgraduate studies (including Ph.D. dissertations). Recently the study of Bartók’s compositional process and the foundation of complex projects are in the forefront of the archive’s activity: the preparations of sample volumes for the Béla Bartók Complete Critical Edition, and the production of the Bartók Thematic Catalogue.

In 2005, László Vikárius became head of the Bartók Archives.

The Budapest Bartók Archives

The Budapest Bartók Archives (in Hungarian: Bartók Archívum) has two functions. It is a central collection of Bartókiana, from primary sources to secondary literature; and at the same time a research institute, a meeting point of international Bartók studies on the life and work of the Hungarian composer, pianist, and ethnomusicologist Béla Bartók (1881–1945).

As a counterpart to Bartók’s estate in the USA, the Budapest Bartók Archives was based on the composer’s manuscripts and library left behind in Hungary. In addition to keeping the second largest collection of compositional autographs, the Archives has a significant collection of documents belonging to his folk-music studies, part of Bartók’s personal library (printed music, books, and periodicals), correspondence, and personal collections (concert programs, newspaper clippings, photos, etc.).

Publications

A select bibliography of recently published or basic studies closely related to the source material of the Bartók Archives.

BARTÓK'S WRITINGS

- Bartók, Béla, Bartók Béla önmagáról, műveiről, az új magyar zenéről, műzene és népzene viszonyáról [Béla Bartók on his life, work, the new Hungarian music, the relation between art music and folk music] = Bartók Béla írásai 1. [Béla Bartók’s Writings vol. 1], ed. by Tibor Tallián (Budapest: Editio Musica, 1989)

- ——, Írások a népzenéről és a népzenekutatásról I. [Essays on folk music and ethnomusicology] = Bartók Béla írásai 3 [Béla Bartók’s Writings vol. 3], ed. Vera Lampert & Dorrit Révész (Budapest: Editio Musica, 1999)

- ——, Írások a népzenéről és a népzenekutatásról II. [Essays on folk music and ethnomusicology] = Bartók Béla írásai 4 [Béla Bartók’s Writings vol. 4], ed. Vera Lampert, Dorrit Révész † and Viola Biró (Budapest: Editio Musica, 2016)

- ——, A magyar népdal (1924) [The Hungarian Folk Song] = Bartók Béla írásai 5. [Béla Bartók’s Writings vol. 5], ed. by Dorrit Révész (Budapest: Editio Musica, 1990)

- ——, Magyar népdalok. Egyetemes gyűjtemény. I. kötet [Hungarian Folk Songs. Complete Edition. Vol. I], ed. by Sándor Kovács and Ferenc Sebő (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1993)

- ——, Magyar népdalok. Egyetemes gyűjtemény. II. kötet [Hungarian Folk Songs. Complete Edition. Vol. II], ed. by Sándor Kovács and Ferenc Sebő (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2007)

FACSIMILE EDITIONS

- Béla Bartók, Sonata (1926) Piano Solo. Facsimile edition of the manuscript with a commentary by László Somfai (Budapest: Editio Musica, 1980)

- ——, Black Pocket-Book (Sketches 1907–1922). Facsimile edition of the manuscript with a commentary by László Somfai (Budapest: Editio Musica, 1987)

- Béla Bartók: Duke Bluebeard’s Castle Opus 11, 1911, Autograph Draft, ed. László Vikárius. Budapest: Balassi Kiadó and Institute for Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2006, and Commentary to Béla Bartók: Duke Bluebeard’s Castle, Op. 11, Facsimile of the Autograph Draft (available in French, German and Hungarian, too)

RECORDS, CD's

- Centenary Edition of Bartók’s Records (Complete) Vols. 1-2. Ed. by László Somfai, Zoltán Kocsis, János Sebestyén (Budapest: Hungaroton, 1981), LPX 12326–38. – (New edition on CD, vol. 1:) Bartók at the Piano. 1920–1945. (Budapest: Hungaroton, 1991), HCD 12326–31; (vol. 2, extended version:) Bartók’s Recordings from Private Collections (Budapest: Hungaroton Classic, 1995), HCD 12334–37

- Somfai, László, ed., Hungarian Folk Music: Gramophone Records with Bartók’s Transcriptions (Budapest: Hungaroton, 1981), LPX 18058–60

CD-ROM

- Bartók Béla 1881–1945. Ed. by György Kroó; consultant László Vikárius (Budapest: Magyar Rádió, Hypermedia Systems, 1995) [Hungarian version, including sketches and fragments]

- Bartók and Arab Folk Music / Bartók és az arab népzene, CD-ROM, ed.: János Kárpáti (editor-in-chief), István Pávai and László Vikárius (Budapest: Hungarian UNESCO, European Folklore Institute and Institute for Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2006)

- Bartók Béla élete – levelei tükrében, Bartók Béla levelei [Béla Bartók’s life in letters, an integrated digital edition of Béla Bartók’s letters published by János Demény, Béla Bartók jun., and Adrienne Gombocz], ed.:István Pávai and László Vikárius (Budapest: MTA Zenetudományi Intézet – Hagyományok Háza, 2007)

DOCUMENTS, STUDIES

- Dille, Denijs, ed., Documenta Bartókiana 1–4 (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1964–1970)

- ——, Thematisches Verzeichnis der Jugendwerke Béla Bartóks 1890–1904 (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1974)

- ——, Béla Bartók. Regard sur le passé. Éd. par Yves Lenoir (Louvain-la-Neuve: Institut Supérieur d’Archéologie et d’Histoire de l’Art, College Érasme, 1990)

- Lampert Vera, “Quellenkatalog der Volksliedbearbeitungen von Bartók” in: Documenta Bartókiana 6 (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1981); new enlarged edition in English: Folk Music in Bartók’s Compositions: A Source Catalog. Arab, Hungarian, Romanian, Ruthenian, Serbian, and Slovak Melodies. (Budapest: Hungarian Heritage House, Helikon Kiadó, Museum of Ethnography, Institute for Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2008), with CD

- Móricz, Klára, „New Aspects of the Genesis of Béla Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra: Concepts of ‘Finality’ and ‘Intention’” in: Studia Musicologica 35/1–3, 1993–94

- Somfai, László, ed., Documenta Bartókiana 5–6 (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1977–1981)

- ——, Béla Bartók: Composition, Concepts, and Autograph Sources (Berkeley–Los Angeles–London: University of California Press, 1996)

- Tallián, Tibor, Béla Bartók, the Man and His Work (Budapest: Corvian, 1988)

- ——, Bartók fogadtatása Amerikában 1940–1945 [Bartók’s reception in America 1940–1945] (Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1988)

- Vikárius, László, „Béla Bartók’s Cantata profana (1930): A Reading of the Sources” in: Studia Musicologica35/1–3, 1993–94

- ——, Modell és inspiráció Bartók zenei gondolkodásában. [Model and inspiration in Bartók’s musical thinking] (Pécs: Jelenkor, 1999)

- Wilheim, András, Mű és külvilág. Három Bartók írás [Work and world. Three Bartók studies] (Budapest: Kijárat Kiadó, 1998)

- ——, ed., Beszélgetések Bartókkal. Interjúk, nyilatkozatok 1911–1945 [Interviews with Bartók 1911–1945] (Budapest: Kijárat Kiadó, 2000)

- Essays in Honor of László Somfai on His 70th Birthday: Studies in the Sources and the Interpretation of Music, ed. László Vikárius and Vera Lampert (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2005)

- Bartók’s Orbit: The Context and Sphere of Influence of His Work. Proceedings of the International Conference held by the Bartók Archives, Budapest (22–24 March 2006), Part I, Studia Musicologica 47, Nos. 3–4 (September 2006), Part II, Studia Musicologica 48, Nos. 1–2 (March 2007)

- Scholarly Research and Performance Practice in Bartók Studies: The Importance of the Dialogue. International Colloquium, Budapest and Szombathely, 2011, Studia Musicologica 53, Nos. 1–4 (September 2012)

A Select Bartók Bibliography

Writings by Bartók in Collected Editions

Bartók Letters in Collected Editions

Studies by Hungarian authors in Hungarian

Studies in English

Studies in other languages

Writings by Bartók in Collected Editions

| Almárné Veszprémi, Lili (ed.) |

Bartók Béla: Önéletrajz - Írások a zenéről [Béla Bartók: Autobiography – Writings on music]. Budapest: Egyetemi Nyomda, 1946 |

| [Almárné Veszprémi, Lili (ed.)] |

Bartók Béla: Önéletrajz - Írások a zenéről. [Béla Bartók: Autobiography – Writings on music]. Introduction by János Demény. Budapest: Egyetemi Nyomda, 1946 |

|

Szabolcsi, Bence – Szőllősy, András (ed.) |

Bartók Béla válogatott zenei írásai [Selected writings by Bartók]. Budapest: Magyar Kórus, 1948. |

|

Szőllősy, András (ed.) |

Bartók Béla válogatott zenei írásai [Selected writings by Bartók]. Budapest: Művelt nép, 1956. |

|

Szőllősy, András (ed.) |

Bartók Béla Összegyűjtött írásai I [Collected writings by Bartók, vol. 1]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó Vállalat, 1967. |

|

Tallián, Tibor (ed.) |

Bartók Béla önmagáról, műveiről az új magyar zenéről, műzene és népzene viszonyáról. Bartók Béla írásai 1 [Bartók on his life and work, on new Hungarian Music, and on the relation between art music and folk music. Writings by Bartók, vol. 1]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1989. |

|

Lampert, Vera – Révész, Dorrit (ed.) |

Írások a népzenéről és a népzenekutatásról. Bartók Béla írásai 3 [Bartók on folk music and folk music research. Writings by Bartók, vol. 3]. Budapest: Editio Musica 1999. |

|

Révész, Dorrit (ed.) |

A magyar népdal. Bartók Béla írásai 5 [Hungarian folk song. Writings by Bartók, vol. 5]. Budapest Editio Musica, 1990. |

|

Carpitella, Diego (ed.) |

Béla Bartók Scritti sulla musica poplare. Torino: Einaudi, 1955. |

|

Hykischová, Eva (ed.) |

Béla Bartók Postrehy a Názory. Translated by Eva Hykischová, Bratislava: Štátne hudobné vydavatel’tsvo, 1965. |

|

Szabolcsi, Bence (Publ.) |

Bartók sa vie et son oeuvre. Paris, Boosey & Hawkes, 1968. |

|

Szabolcsi, Bence (ed.) |

Béla Bartók Musiksprachen. Aufsätze und Vorträge. Leipzig: Reclam, 1972. |

|

Szabolcsi, Bence (ed.) |

Weg und Werk Schriften und Briefe. Budapest: Corvina, 1972. |

|

Suchoff, Benjamin (ed.) |

Béla Bartók Essays. London: Faber & Faber, 1976. |

|

Autexier, Philippe A. |

Musique de la vie. Autobiographie, lettres et autres écrits. Trad. par Autexier Budapest: Paris: Stock Musique 1981. |

|

Suchoff, Benjamin (ed.) |

Béla Bartók Studies in Ethnomusicology. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. |

|

Wilheim, András (ed.) |

Beszélgetések Bartókkal. Nyilatkozatok, interjúk 1911–1945 [Interviews with Bartók. 1911–1945]. Budapest: Kijárat Kiadó, 2000. |

Bartók Letters in Collected Editions

|

Demény, János (ed.) |

Béla Bartók Letters. Translated by Péter Balabán and István Farkas, Budapest: Corvina, 1971. |

|

Demény, János (ed.) |

Béla Bartók Briefe. Übersetzt von Mirza Schüchig, Budapest, Corvina, 1973. |

|

Demény, János (ed.) |

Bartók Béla levelei [Béla Bartók Letters] Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1976. |

|

László, Ferenc (ed.) |

Béla Bartók Scrisori, 2 vols. Translated by Gemma Zimveliu, Bukarest: Kriterion, 1976. |

|

Bartók, Béla, Jr. and Adrienne Gombocz–Konkoly (ed.) |

Bartók Béla családi levelei [Family Letters of Béla Bartók] . Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1981. |

Studies by Hungarian authors in Hungarian

|

Balázs, Béla |

A Kékszakállú herceg vára. Kass János rajzaival, Kroó György utószavával [Duke Bluebeard’s Castle. With illustrations by János Kass and an afterword by György Kroó]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1979. |

|

Bartók, Béla |

Cantata Profana. A kilenc csodaszarvas. Kroó György előszavával, Réber László rajzaival [The Nine Enchanted Stags. With an introduction by György Kroó and illustrations by László Réber]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1974. |

|

Bartók, Béla Jr. |

Apám életének krónikája [The Chronicle of My Father’s Life]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1981. |

|

Bartók, Béla Jr. |

Bartók Béla műhelyében [The Workshop of Béla Bartók]. Budapest: Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, 1982. |

|

Bónis, Ferenc |

Béla Bartók. His Life in Pictures and Documents. Translated by Lili Halápy, Budapest: Corvina, 1972. |

|

Bónis, Ferenc |

Így láttuk Bartókot. Harminchat emlékezés [Bartók Remembered: 36 Recollections]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1981. |

|

Kárpáti, János |

Bartók-analitika. Válogatott tanulmányok [Bartók Analitics. Selected Studies]. Budapest: Rózsavölgyi és Társa, 2003. |

|

Kovács, Sándor |

Bartók Béla [Béla Bartók]. Budapest: Mágus, 1995. |

|

Kroó, György |

A Guide to Bartók. Translated by Ruth Pataki and Mária Steiner, Budapest: Corvina, 1974. |

|

Lampert, Vera |

Bartók népdalfeldolgozásainak forrásjegyzéke [Source Catalogue of Bartók’s Folksong Arrangements]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1980. |

|

László, Ferenc |

Bartók Béla. Tanulmányok és tanúságok [Béla Bartók. Sudies and Testimonies]. Bukarest: Kriterion Könyvkiadó, 1980. |

|

Lendvai, Ernő |

Bartók költői világa [Bartók’s Poetical World]. Budapest: Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, 1971. |

|

Lendvai, Ernő |

Bartók stílusa a „Szonáta két zongorára és ütőhangszerekre” és a „Zene húros-, ütőhangszerekre és celestára” tükrében [Bartók’s Style as Reflected in the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion and Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó Vállalat, 1955. |

|

Somfai, László |

Tizennyolc Bartók-tanulmány [Eighteen Bartók Studies]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1981. |

|

Tallián, Tibor |

Bartók fogadtatása Amerikában 1940-1945 [Bartók’s Reception in America 1940-1945]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1988. |

|

Tallián, Tibor |

Cantata profana – Az átmenet mítosza [Cantata Profana – Rite of Passage]. Budapest: Gyorsuló idő, 1983. |

|

Ujfalussy József |

Bartók breviárium. (levelek–írások–dokumentumok) [A Bartók Reader (Correspondence, Essays and Documents)]. Budapest: Zeneműkiadó, 1980. |

|

Vikárius László |

Modell és inspiráció Bartók zenei gondolkodásában. A hatás jelenségének értelmezéséhez [Model and Inspiration in Bartók’s Musical Thinking]. Pécs: Ars Longa, Jelenkor Kiadó, 1999. |

Studies in English

|

Bartók, Péter |

My Father. Homosassa, Florida: Bartók Records, 2002 |

|

Frigyesi, Judit |

Béla Bartók and the Turn-of-the-Century Budapest. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1998 |

|

Gillies, Malcolm |

Bartók in Britain. A Guided Tour. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989 |

|

Gillies, Malcolm |

Bartók Remembered. London, Boston: Faber and Faber, 1990 |

|

Kroó, György |

Bartók Béla színpadi művei. [Bartók’s Stage Works] Budapest: Zeneműkiadó Vállalat, 1962. |

|

Laki, Péter (ed.) |

Bartók and his World. Princenton: University Press, 1995 |

|

Leafstedt, Carl S. |

Inside Bluebeard's Castle. Music and Drama in Béla Bartók's Opera. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999 |

|

Lendvai, Ernő |

Béla Bartók. An Analysis of his Music. With an introduction by Alan Bush. London: Kahn & Averill, 1971 |

|

Lendvai, Ernő |

The Workshop of Bartók and Kodály. Budapest: Editio Musica, 1983 |

|

Somfai, László |

Béla Bartók Composition, Concepts, and Autograph Sources. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1996 |

|

Stevens, Halsey |

The Life and Music of Béla Bartók. New York, Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1953 |

|

Suchoff, Benjamin |

Guide to the Mikrokosmos. (Genesis, Pedagogy, and Style) Lanham, Maryland, and Oxford: The Scarecrow Press. Inc. 2002 |

|

Tallián, Tibor |

Béla Bartók. The Man and His Work. Translated by Gyula Gulyás, Budapest: Corvina, 1988 |

|

Ujfalussy, József |

Béla Bartók. Translated by Ruth Pataki, Budapest: Corvina, 1971 |

Studies in other languages

|

Bónis, Ferenc |

Béla Bartók. Sein Leben in Bilddokumenten. Übersetzt von Irene Kolbe, Budapest: Corvina, 1972 |

|

Dille, Denijs |

Bela Bartok. Antwerpen: Metropolis, 1974 |

|

Dille, Denijs |

Béla Bartók. Regard sur le passé. ed Yves Lenoire, Louvain-la Neuve: Institut Supérieur d’Archéologie et d’Histoire de l’Art, Collège Érasme, 1990 |

|

Dille, Denijs |

Généalogie sommaire de la famille Bartok. Antwerpen: Metropolis, 1977 |

|

Fuchss, Werner |

Béla Bartók und die Schweiz. Eine Dokumentensammlung. Bern: Publikation ser Nationalen Schweizerischen UNESCO-Komission, 1973 |

|

Gillies, Malcolm |

Béla Bartók im Spiegel seiner Zeit. Portraitiert von Zeitgenossen. Übersetzt von Wiebke Falckenthal, Zürich, St. Gallen: Edition Musik & Theater, 1991 |

|

Kroó, György |

Bartók-Handbuch. Übersetzt von Erzsébet Székács, Budapest: Corvina, 1974 |

|

Moreux, Serge |

Béla Bartok sa vie – ses oeuvres – son langage. Paris: Richard-Masse, 1949 |

|

Tallián, Tibor |

Béla Bartók. Sein Leben und Werk. Übersetzt von Susanne Rauer Farkas und Jürgen Gaser, Budapest: Corvina, 1988 |

|

Ujfalussy, József |

Béla Bartók. Übersetzt von Sophie und Robert Boháti, Budapest: Corvina, 1973 |

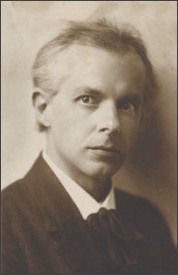

Béla Bartók

(25 March 1881 – 26 September 1945)

Béla Bartók’s life and work seem particularly relevant during a period of European integration that is just happening before our eyes and to an extent that was previously certainly never even dreamt of, especially not during the composer’s life when Europe was repeatedly divided by two “World Wars.” Bartók’s unquenchable interest in (and, as he himself expressed, love for) the peasant music of different nations, ethnicities, groups and territories has set an unparalleled example for us today.

Béla Bartók, composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist, was born in Nagyszentmiklós in Hungary (now Sînnicolau Mare in Romania) in 1881 and died in New York in 1945. His childhood was plagued with various illnesses. After the early death of the father (Béla Bartók, Sr.), when he was only seven years old, his mother, Paula Voit, struggled to raise her two children, Béla and her then three-year-old daughter, Elza, wandering from town to town before finally settling in Pozsony (Pressburg, now Bratislava, Slovakia) where Béla received thorough musical instruction and completed his grammar school studies. Following in Ernő (Ernst von) Dohnányi’s footsteps, four years his senior and also coming from Pozsony, he studied piano (with Liszt pupil István Thomán) and composition (with Hans Koessler) at the Budapest Royal Academy of Music between 1899 and 1903. Although he was immediately recognized as a powerful talent as both pianist and composer, his career was not an easy one. After writing his first grand-scale “nationalist” compositions (notably the Kossuth Symphony, a work soon withdrawn, the Rhapsody for piano and for piano and orchestra, and the First Orchestral Suite), he discovered peasant music as a more indigenous and more “authentic” source of something particularly “Hungarian” in music and began to collect folk music on a regular basis and to write modern, often experimental works (Fourteen Bagatelles for piano, First String Quartet) using folk music-derived modernistic material. The development of his new musical style was also influenced by the personal crisis of his unrequited love towards the violinist Stefi Geyer in 1907–1908 whose crucial artistic document is the posthumously published (“1st”) Violin Concerto. In 1909 he married Márta Ziegler who bore him his first son Béla Bartók, Jr. (1910–1994). Besides being piano professor at the Academy of Music in Budapest from 1907 on, Bartók gradually developed into a full-scale scholar. For more than a decade, he devoted most of his energies to field trips to remote areas of pre-First-World-War Hungary that also included large areas of partly or mainly Slovak and Romanian speaking ethnic groups. Quite early in his research, Bartók turned to the collection of folk music from the minorities as well thereby significantly contributing to the then new field of comparative ethnomusicology. He was particularly interested in archaic features of peasant music that he described as a “natural phenomenon” whose study should be considered as “scientific” work. His extensive collections in Hungary include some 3500 Romanian, 3000 Slovak and 2700 Hungarian, as well as some Serbian and Bulgarian melodies.

Béla Bartók, composer, pianist and ethnomusicologist, was born in Nagyszentmiklós in Hungary (now Sînnicolau Mare in Romania) in 1881 and died in New York in 1945. His childhood was plagued with various illnesses. After the early death of the father (Béla Bartók, Sr.), when he was only seven years old, his mother, Paula Voit, struggled to raise her two children, Béla and her then three-year-old daughter, Elza, wandering from town to town before finally settling in Pozsony (Pressburg, now Bratislava, Slovakia) where Béla received thorough musical instruction and completed his grammar school studies. Following in Ernő (Ernst von) Dohnányi’s footsteps, four years his senior and also coming from Pozsony, he studied piano (with Liszt pupil István Thomán) and composition (with Hans Koessler) at the Budapest Royal Academy of Music between 1899 and 1903. Although he was immediately recognized as a powerful talent as both pianist and composer, his career was not an easy one. After writing his first grand-scale “nationalist” compositions (notably the Kossuth Symphony, a work soon withdrawn, the Rhapsody for piano and for piano and orchestra, and the First Orchestral Suite), he discovered peasant music as a more indigenous and more “authentic” source of something particularly “Hungarian” in music and began to collect folk music on a regular basis and to write modern, often experimental works (Fourteen Bagatelles for piano, First String Quartet) using folk music-derived modernistic material. The development of his new musical style was also influenced by the personal crisis of his unrequited love towards the violinist Stefi Geyer in 1907–1908 whose crucial artistic document is the posthumously published (“1st”) Violin Concerto. In 1909 he married Márta Ziegler who bore him his first son Béla Bartók, Jr. (1910–1994). Besides being piano professor at the Academy of Music in Budapest from 1907 on, Bartók gradually developed into a full-scale scholar. For more than a decade, he devoted most of his energies to field trips to remote areas of pre-First-World-War Hungary that also included large areas of partly or mainly Slovak and Romanian speaking ethnic groups. Quite early in his research, Bartók turned to the collection of folk music from the minorities as well thereby significantly contributing to the then new field of comparative ethnomusicology. He was particularly interested in archaic features of peasant music that he described as a “natural phenomenon” whose study should be considered as “scientific” work. His extensive collections in Hungary include some 3500 Romanian, 3000 Slovak and 2700 Hungarian, as well as some Serbian and Bulgarian melodies.

From 1906, he often worked together with fellow composer and ethnomusicologist Zoltán Kodály (1882–1967). In search of ancient musical cultures, Bartók even collected rural Arab songs in Algeria in 1913 and later he visited Turkey in 1936. His collecting activity, however, practically ended in 1918 soon before the partitioning of Hungary in the wake of the First World War and the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire when fieldwork on territories with some of the richest folklore traditions became impossible. Instead, he carried on his ever more detailed scholarly transcriptions and systematization of his Slovak and Romanian collections. In the meantime he also published the first scholarly monograph on Hungarian peasant songs (A magyar népdal, 1924, Das ungarische Volkslied, 1925, Hungarian Folk Music, 1931) that also included a large selection of examples. Between 1934 and 1940, he worked on the preparation of an edition of the 13,000 Hungarian songs collected by then and preserved at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. In 1937/38, he was also involved with a series of recordings for the Pátria series. For his ethnomusicological work he became elected member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 1935.

By the end of the First World War, especially after the successful premières of his two stage works (to librettos by Béla Balázs), the ballet, The Wooden Prince (1914–17), and the opera, Duke Bluebeard’s Castle (1911) in 1917 and 1918, respectively, he had established himself as the leading composer of his generation in Hungary. From 1918 on, his compositions were published by Universal Edition, Vienna, and he could start to build up an international career as pianist and, more importantly, composer regularly visiting Paris, London and other musical centres of Europe. He also toured the United States and the Soviet Union in the later 1920s.

1923 marks his divorce from his first wife and his marriage with his young pianist pupil, Ditta Pásztory. Their child, Péter Bartók, was born in the following year.

Bartók’s piano music, e.g. Allegro barbaro (1911) and Outdoors (1926) and his pedagogical compositions, e.g. For Children (1908–1911) and Mikrokosmos (1932–39), as well as the Forty-Four Violin Duos (1931) occupy a significant place in 20th-century composition, and his six String Quartets (composed between 1908 and 1939) are considered among the finest modern representatives of the genre. Some of his larger scale orchestral works also had a significant world-wide success from their first performances, especially the Dance Suite (1923) and Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936), the first of his compositions commissioned by the Swiss conductor and patron Paul Sacher. His pantomime, The Miraculous Mandarin (1918–19, orchestration 1924 on a scenario by Menyhért (Melchior) Lengyel), is probably his most daringly and most radical modernist masterpiece whose subject matter caused outrage at its première in Cologne in 1926. These works put him close to the rank of Schoenberg and Stravinsky, the two most famous composer innovators of his generation. As lecturer, author of numerous studies and articles, and editor of extensive volumes of folksong collections, Bartók was considered as a leading authority on East-European folklore.

Following Nazi Germany’s occupation of Austria, he changed publishers to the London based Boosey and Hawkes and started to arrange for his departure from threatened Hungary and Europe and, in 1940, he went to the United States. Apart from giving concerts, he was mainly occupied at Universities, Columbia University, from which he received an honorary doctorate and where he worked at the transcription and systematization of Milam Parry’s South Slavic collection, and Harvard University. During his American exile, his fatal illness, leukaemia, soon made its appearance. Still, he was able to compose some great masterpieces, such as the Concerto for Orchestra (for conductor Serge Koussevitzky, 1943), the Sonata for Solo Violin (for the violinist Yehudi Menuhin, 1944) and his Third Piano Concerto written for his wife, and he was able to complete the preparation for publication of most of his folk music collections, which were, however, published only posthumously.

While during and immediately after the war he was deeply concerned with his homeland’s fate and future, and he never gave up his Hungarian citizenship, he did not consider it timely to return to Hungary. Decades after his death, his remains were solemnly transferred from New York to Budapest by his two sons and reburied at the Farkasrét Cemetery where it now rests.